Fantasy Living Room Decor

Are these the ultimate fantasy homes?

(Image credit:

Richard Powers

)

From the flamboyant to the ultra-modern and the visionary, these are some of the most stunning dream interiors of the past 100 years. What makes them so iconic?

H

How do you define 'iconic' in the world of design? For some time, the word has been blithely bandied about to describe a new building, which, it is hoped, will become a well-known landmark or provide a city with cultural kudos. On closer consideration, the word is slippery, capable of meaning many things. It can suggest a global fame and popularity garnered by a building such as the Eiffel Tower in Paris – now emblematic of an entire city. Or it can describe a designer's quintessential project – one that truly sums up his or her work.

More like this:

- A home where 'body and soul can rest'

- The art of elegant compact living

- Hideaways designed for tranquility

A thoughtful evaluation of 20th and 21st-Century domestic interiors currently exerts a huge fascination in the design world – and prompts questions about what iconic means in this context. A new book, The Iconic Interior, by Dominic Bradbury with photographs by Richard Powers, is a thumping tome that explores the evolution of extraordinary homes around the world, from around 1900 to the present. An updated edition of his 2012 book, it features around 600 images of extraordinary houses.

Brazilian architect Lina Bo Bardi's 1951 Casa de Vidro is a dream home par excellence

Bradbury is aware of the trite over-use of the word iconic: "I'm always suspicious of those who claim a brand new project is iconic, since only time will tell," he says. Instead, he believes, a house comes to be seen as iconic organically: "Most architects and designers just set out to do their best rather than aim to create something iconic. For me, an iconic interior has influence well beyond the original ambition of a project and takes on a life as a key reference point in the wider world."

Meanwhile, the exhibition Home Stories: 100 Years, 20 Visionary Interiors, organised by the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein in Germany, also focuses on the history of homes over a similar period. Although currently closed, the museum now plans to extend the show beyond the summer. Its accompanying catalogue features essays by leading design writers, curators and designers who examine the influence of politics, major social changes and technological advances on interiors.

Danish architect Finn Juhl's 1941 interior for a home in Ordrup, Denmark has a modern, elegant feel

"We've seen an interest in domestic interior design as a discipline for some time, yet it seems to have lacked a serious discourse until now," says the exhibition's curator Jochen Eisenbrand. "It's mainly dealt with in superficial ways – in glossy magazines, TV shows and social media. We wanted to show important historical examples as an inspiration for a more serious discussion."

The exhibition spotlights diverse interiors by such key figures as Austrian architect Adolf Loos, Danish architect Finn Juhl, Italian-born Brazilian architect Lina Bo Bardi, US interior designer Elsie de Wolfe, artist Andy Warhol and photographer Cecil Beaton.

Both book and show feature interiors designed by women who are less well-known than many of their male counterparts. One point raised by the show is the sexist distinction once made between interior decoration, an amateur occupation usually undertaken by 'housewives' or women from affluent backgrounds, and architecture, a serious profession practised by men.

Interior designer Elsie de Wolfe was known for her light touch and uncluttered spaces

One example of the former was Edith Wharton, the novelist, whose interiors are featured in both show and book, as are those of Elsie de Wolfe, a former actress turned interior decorator. In 1914, De Wolfe furnished 14 rooms in the Frick Residence in New York, a building in the French Neoclassical style. She was known for her light touch – a preference for uncluttered interiors, sparingly furnished with unimposing French antiques.

The exhibition catalogue features an essay by design writer Alice Rawsthorn entitled Interior Design – A Matter of Gender? In it, she points out how difficult it was for women in the 19th Century to work in interior design, with the notable exception of well-connected British cousins Rhoda and Agnes Garrett. Agnes's sisters Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Britain's first woman doctor, and Millicent Garrett Fawcett, the women's suffrage campaigner, commissioned them to design the interiors of their homes. "The Garretts swiftly became known for a subtly elegant, utilitarian and comfortable style of interiors that contrasted sharply with the typically fussy, gaudy British homes of the era," writes Rawsthorn, author of the book Design as an Attitude.

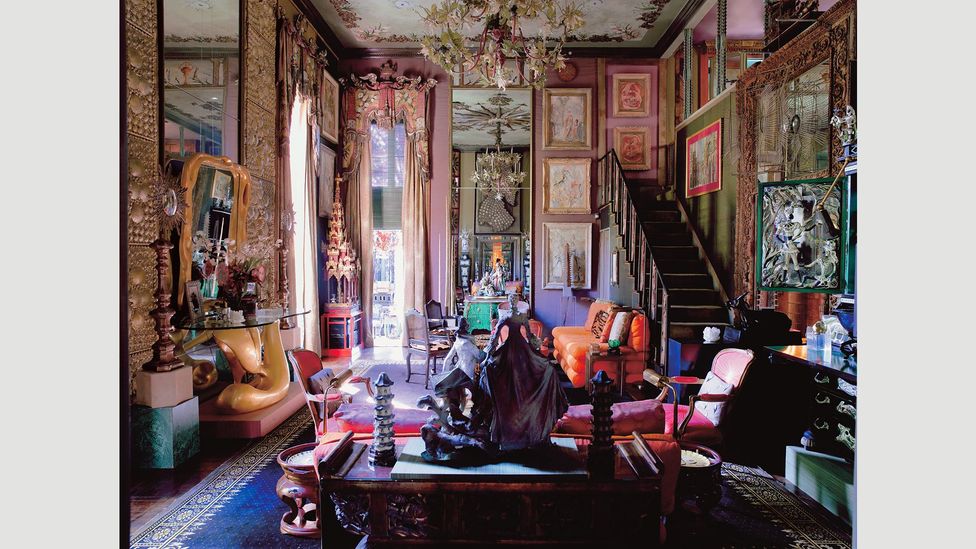

Tony and Elizabeth Duquette created Dawnridge after their marriage in 1949

The show also takes in social housing. In 1926, German architect and city-planner Ernst May began to oversee Frankfurt's highly acclaimed affordable public housing project, New Frankfurt, built in response to a housing shortage and completed in 1930. Its emphasis on efficient use of space, in particular in kitchens, was inspired by US home economist Christine Frederick, an advocate of Taylorism applied to interior design. Austrian architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotsky made a significant contribution to the project, creating the prototype for a built-in kitchen – a template for the modern, streamlined, fitted kitchen. The dimensions and layout of this compact, labour-saving, low-cost design were based on Taylorist principles and research regarding the number of footsteps necessary to perform various tasks. Around 10,000 Frankfurt kitchens, as they are known, were installed in working-class apartments in the city in the late 1920s.

Flamboyant and fantastical

In contrast to the early 20th-Century movement for affordable, practical homes, but running parallel to it was a trend for individualistic abodes with flamboyant, fantastical decors. "Cecil Beaton's house Ashcombe, an extremely individual home unrestrained by tradition and notions of good taste, was almost a stage set," says Eisenbrand. Beaton rented this Georgian manor house in Wiltshire in the English countryside from 1930 to 1945, inviting stage designer Oliver Messel to paint murals there, and entertaining everyone from actress Tallulah Bankhead to artist Salvador Dalí in his home.

The salon at Cecil Beaton's house Ashcombe, which was decorated in a flamboyant, individualistic style

Similarly outlandish was Dawnridge in Los Angeles, co-created by Tony Duquette, a costume and set designer for Hollywood movies, and architect Casper Ehmcke in 1949. Duquette stuffed it with seashell-encrusted screens, chandeliers dripping with glass lilies, multiple mirrors to create the illusion of more space, elaborate architectural maquettes, and sofas covered in orange or shocking pink fabrics.

The show also highlights how the rebellious spirit and increasingly relaxed lifestyles of the 1960s resulted in more informal interiors. Paradoxically, an iconoclastic interior can become regarded, over time, as iconic. Take Andy Warhol's 1960s Silver Factory in New York – a trailblazer for loft-living, and a major inspiration behind the industrial aesthetic found in countless interiors ever since.

French architect Claude Parent created an 'anti-rationalist' apartment in 1973-74

Eisenbrand sees the Silver Factory, whose walls were spray-painted silver, and lined with tin foil by photographer Billy Name, as influential on several levels: "It's arguably the most famous example of loft-living because it has been photographed and filmed so much. It's also a good example of the artist's studio as nexus for living and working, and of communal living in the 1960s. It reflects urban development at the time: it typifies the rise of loft-living in Manhattan, triggered by industry moving out of inner-city areas. "Meanwhile, influential French architect Claude Parent, in collaboration with cultural theorist Paul Virilio, challenged the Modernist convention of the cube-like interior when he designed his anti-rationalist apartment in Neuilly-sur-Seine, near Paris from 1973 to 1974. Parent considered vertical planes pedestrian, ousting them in favour of eccentric sloping floors, intended as multifunctional surfaces adaptable as seating, workspaces and daybeds. Admirers of his so-called 'oblique architecture' have included architects Frank Gehry and Zaha Hadid.

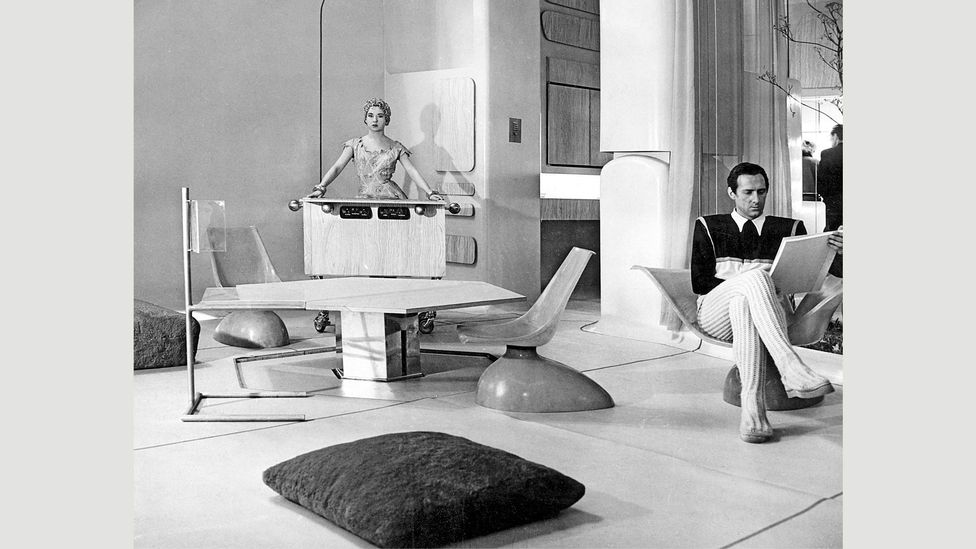

Alison and Peter Smithson House of the Future, 1956, was featured in the Ideal Home Exhibition

In some cases, homes have become iconic because architects assiduously publicised their projects, or because widespread media coverage brought them recognition. "Lina Bo Bardi published her Casa de Vidro project in the magazine Habitat that she published," says Einsenbrand. "Beaton's place Ashcombe was featured in Vogue and Sketch magazines and in the book he wrote about it. Another iconic home, architects Alison and Peter Smithson's House of the Future of 1956, was conceived for The Daily Mail Ideal Home Exhibition which guaranteed media exposure in the paper and in TV documentaries."

Many homes in the book The Iconic Interior were created by high-profile architects for themselves or for adventurous clients. Others were inhabited by creatives, including artists and designers, who treated them as spaces where they gave free rein to their taste. At Charleston, the East Sussex farmhouse that Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell rented from 1916, busily hand-painted walls testify to the equal importance Bloomsbury Group artists gave to fine art and the decorative arts.

Charleston is the countryside farmhouse that the Bloomsbury Group made their own, hand painting the walls

One of the earliest homes featured in the book is Villa Esche in Germany, designed in 1903 by Belgian artist and architect Henry van de Velde for Herbert Esche, a businessman and patron of the arts. The 32-room villa, with all furniture designed by Van de Velde, was in the forward-looking Art Nouveau style, which represented a major watershed in interiors by rejecting all past architectural styles, and often espousing asymmetric forms inspired by nature.

An interior can become iconic because it was radically unorthodox and ahead of its time, as Bradley points out: "Adolf Loos is a famous example of someone who openly challenged convention". Loos was an early proponent of Modernism and this book includes his sparsely furnished Steiner House in Vienna, designed in 1910. That year, Loos delivered his lecture, Ornament and Crime, which lambasted the domestic clutter of the Victorian era. "The evolution of culture marches with the elimination of ornament from useful objects," he proclaimed.

Even so, early 20th-Century Art Deco flouted doctrinaire functionalism. A striking 1920s example is couturière Jeanne Lanvin's opulent Paris apartment, designed by Armand-Albert Rateau. Its bedroom, whose walls were lined with silk in lapis-lazuli blue, was later reassembled and is exhibited at Paris's Musée des Arts Décoratifs. Although mainly known as an Art Deco designer, Rateau's approach was eclectic, drawing inspiration, too, from Neoclassicism and Japanese decorative arts.

Architect Berthold Lubetkin's penthouse features natural materials such as rough-cut timber

By the 1930s, a softer, more organic take on Modernism was emerging, exemplified by Soviet émigré architect Berthold Lubetkin's penthouse in his building Highpoint II in Highgate, London. Here natural materials abounded, including rough-cut lengths of timber lining the walls and brown tiled floors.

Deep in woodland in the River Hudson Valley in New York State, designer Russell Wright made even more of a virtue of natural materials in his bid to unite nature and architecture with his proto-eco house Dragon Rock, built into a hillside in 1961. "The house should complement this tiny part of the world. We should preserve its beauty," noted Wright. Exposed, rugged granite and cedar trees form part of the house's fabric, the fireplace was constructed from boulders, while his green-roofed studio stood a short distance away, its desk overlooking the woods.

Designer Russell Wright built his proto-eco house Dragon Rock in 1961 to complement its surroundings

Other celebrated modernist projects include the expansive Strick House in Santa Monica, California designed by Oscar Niemeyer in 1964, a largely glass-fronted house whose high-ceilinged living room overlooks a swimming pool and garden. The book also features the Niemeyer-inspired Milan House in São Paulo, designed by Marcos Acayaba in 1975, which comprises a curved concrete roof containing three interconnected levels that visually connect with tropical gardens surrounding the building.

By the 1960s and 1970s, US architects – and husband and wife – Roberto Venturi and Denise Scott Brown were radically questioning Modernism and ushering in Postmodernism. They celebrated and rehabilitated architectural elements long banished by Modernism, such as historicism and ornamentation. In Venturi's 1966 book, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, he coined his witty riposte to modernist architect Mies van der Rohe's earnest dictum "Less is more" – "Less is a bore". In the 1972 tome, Learning from Las Vegas, which he co-wrote with Scott Brown and Steve Izenour, he recognised a vitality in the brash, pastiche architecture of Las Vegas that clean-lined, rationalist modernist architecture lacked.

The couple moved into their Art Nouveau-style home, Venturi House, in Philadelphia, furnishing its dining room with chairs painted a blackcurrant-fool shade and inscribing its walls with the names of their illustrious but ill-assorted heroes, from Neoclassical architect John Soane to arch-modernist Le Corbusier. The living room was gleefully eclectic, kitsch and ironic, combining walls stencilled with floral motifs, a pop parody of a Vermeer painting, Italian designer Gae Aulenti's 1966 Pipistrello lamp with an Art Nouveau-style shade and a flamingo-pink neon strip light.

A São Paulo home designed by Marcos Acayaba in 1975 is among those featured in Dominic Bradbury's book The Iconic Interior

A later example featured in the book is the idiosyncratic London apartment of industrial designer Marc Newson, co-created with architects Squire & Partners in 2010. It's inspired by the Swiss chalet in Alfred Hitchcock 's 1959 movie North by Northwest, and one wall in its theatrical living room is studded with stones sourced from a river in Nova Scotia.

Naturally, books such as The Iconic Interior help to confer iconic status on homes by featuring them. Even looking at images of homes not open to the public raises awareness of them and gives them an appealing mystique. "My book mixes homes that can be visited with others that remain private," says Bradbury. "The latter have to work harder to gain recognition. But some achieve an almost mythical status."

The Iconic Interior by Dominic Bradbury is published by Thames & Hudson.

For more information on Home Stories: 100 Years, 20 Visionary Interiors, visit the Vitra Design Museum website.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us onTwitter .

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter , called The Essential List, a handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20200414-are-these-the-ultimate-fantasy-homes

0 Komentar